Why Do We Learn New Languages?

Many people around the world learn two or three languages during their lifetime. Sometimes their motivation is to speak with relatives and neighbors, sometimes for a job or travel, sometimes for the love of a culture or a heritage. Parents of young learners often consider the benefits of learning a language as an investment in education and employment opportunities. Many people recognize the cognitive value of bilingualism as well.

Around the world, English is the most popular additional language for people to learn for personal, academic, or professional purposes. The global marketplace and the increasing use of English-medium instruction in schools contributes to the need for learners to strengthen their English skills. The English language classroom that uses up-to-date teaching methodologies is an excellent place to acquire 21st-century skills such as communication, collaboration, creativity, and intercultural competence.

Content-based English, where students study academic English through cross-curricular content, is an ideal approach for developing students’ English language fluency and literacy for success in school and beyond. Although college and career may seem far away to students in primary grades, these goals are present in their parents’ and teachers’ minds.

How Do Young Learners Develop Academic English Skills?

The way that young learners develop academic English is the same as the way they learn any subject—through engagement. Young learners are curious about their world and that curiosity prompts them to explore, read, talk, and create. When we harness that curiosity and combine it with interactive instruction, we create conditions that foster language learning.

Let’s discuss four key elements of instructional units that help young learners acquire curricular subject area knowledge and academic English language skills in meaningful and engaging ways: Addressing a Big Question, Ramping up Vocabulary Development, Combining Informational and Narrative Text, and Making Real World Connections.

Addressing a Big Question

Organizing a unit of study around a Big Question motivates students to tell what they know about a topic and encourages them to find out more. A Big Question places inquiry at the center of learning. It should highlight a critical issue and create student interest. It should not have a simple answer but should invite multiple perspectives, unique ideas, and personal connections. Big questions for young learners in Reach Higher include “What does it take to survive?”, “How do treasures shape our past and future?”, and “When is something alive?”

With a thought-provoking question guiding them, students can use discussion, reading, and writing as tools to expand and grow ideas. We also know that students who read because they are curious about a topic achieve better comprehension of the text than those students who read simply to complete the task. A Big Question therefore makes reading more purposeful.

When a Big Question is introduced at the beginning of a unit, the teacher can build a concept map that lists what students already know about the topic as well as they want to know. Then, as a class, they can have a common goal of investigating the topic. Teachers can also use a Big Question as a jumping off point for vocabulary, phonics, grammar, and writing instruction and provide students with opportunities to be creative while integrating their growing knowledge of the content and English through oral presentations and writing projects.

Ramping up Vocabulary Development

In order to discuss the Big Questions effectively, young learners need to use new content-specific words and phrases and general academic terms. To do this requires explicit instruction and repeated practice. Each unit introduces key content-specific words that correspond to the science or social studies topic and key academic words that are cross-curricular (like discovery, interpret, and examine). These words are carefully selected and directly taught to augment the students’ understanding of the topic, prepare them for the reading selections, and scaffold their ability to have academic discussions. Repeated practice–through reading and writing tasks and structured opportunities for talk–moves these words into long-term memory and lets students make words their own.

Direct teaching of specific key words facilitates vocabulary growth and increases reading comprehension but it is not sufficient. That is why Reach Higher also teaches strategies for word learning, such as examining context clues and word parts (e.g., roots and prefixes), and encourages students to consider native language cognates as sources of meaning. Young learners also participate in a wide range of word-building activities such as playing vocabulary games, retelling stories from illustrations, and writing chants and songs.

Combining Informational and Narrative Text

Traditional language instruction uses texts that tell stories and are controlled for vocabulary and sentence structure. The reading selections in Reach Higher are different. By using authentic literature and a combination of informational and narrative text, students are better prepared for academic instruction. Each unit in Reach Higher supports the inquiry approach with thematically paired fiction and non-fiction, organized in service of the Big Question. The Big Question sparks student interest and encourages their quest for answers in the text. As students read the main selections and shorter pieces, they acquire knowledge of the concept and new perspectives that they can use to dialogue with their peers and respond to the question.

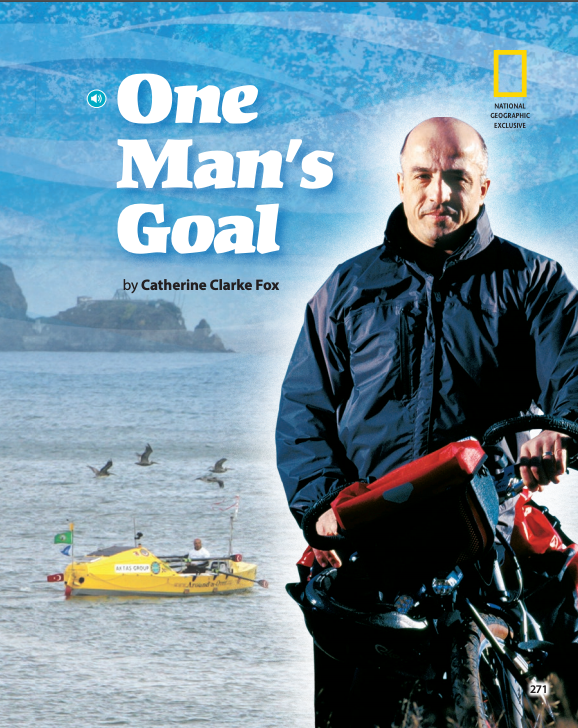

Many of these informational texts are related to the work that National Geographic does in science and social studies, and they are accompanied by exquisite photographs and video clips. The photos and videos help the learners build background knowledge so they can make meaning from the text. Students learn to use the text features embedded in the passages too. Science articles, for example, have accompanying charts and diagrams. Social studies selections have maps, photos of artifacts, and other graphic supports.

Making Real World Connections

Academic standards are particularly concerned with real-world application of scientific and mathematical knowledge. Reach Higher presents an exciting way to achieve this objective. The National Geographic explorers, showcased in many texts, truly exemplify science in action. While reading about the explorers’ research-driven adventures, students learn about the scientific method, the need for repeated trials when testing a hypothesis, the use of mathematical models, and the joy of discoveries. As students revisit the Big Question throughout each unit, they must apply the new knowledge they have acquired. They may change their responses as new information comes to light, just as scientists and mathematicians do.

For young learners of English, these real-world connections are quite valuable. Many of the reading passages associated with the marine biologists, geographers, wildlife photographers, and others take place in their geographic regions. Some may be working in the students’ home countries. In this regard, the students’ knowledge becomes an asset in both making meaning of the text and in applying the knowledge to their personal settings.

Reach Higher prepares young learners for English-medium classes by giving them practice with key academic language and content topics. The lessons give students opportunities to learn key academic and subject-specific vocabulary, read related fiction and nonfiction texts, and apply new knowledge to real-world situations while investigating a Big Question. By infusing content in reading, writing, and oral language practice, Reach Higher lessons equip students with the knowledge and skills they need for success in school.

If you haven’t had a chance to see it, be sure to watch Deborah Short’s recent webinar recording here!

Hello my name is Evelin I live in Mexico, my curiosity for languages began when I was young I couldn’t speak properly, when I pronounced some words my tongue was constantly stuck even in my own language, so I decided to start studying another language maybe that would help my pronunciation, with time and keep practicing it helped me a lot to improve, I think that speaking a different language is important academic, professional and also for simple as the pronunciation.