This blog post is a follow-up to a webinar I gave a few weeks ago. The webinar addressed this question: How do we avoid overwhelming our learners when we present them with new topics and information-rich texts and then ask them to discuss and analyze them in a meaningful way? This is a problem especially with students preparing for university study, but it applies to other learners too.

There are two keys to unlocking this problem and they both lie in the realm of critical thinking. One key is to constantly demand of students that they reflect. The other key is to help them to build background knowledge, because this is also an often-overlooked aid to critical thought.

Reflecting

Reflective thinking is the cornerstone of critical thinking. It means being curious about the thing in front of you: whether that’s the language, the topic, or the medium you’re receiving the information through.

Prompting reflection is not a difficult thing to do. It often just means asking ‘why’? We just need to remember to do it. Because the more we do it, the more our learners begin to develop a critical mindset of their own.

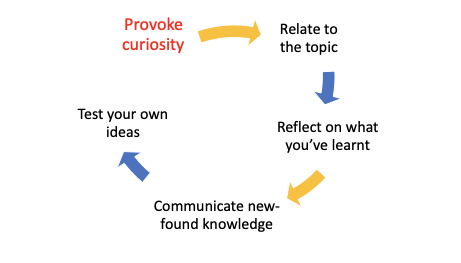

A given lesson should first provoke students’ curiosity about a topic (What’s this about?). Then it should then invite them to relate to the topic (What is there in my personal experience that links to this subject?). When they have processed the new information, they must then reflect on what they’ve learned (What are the key takeaways from this?) and consider how they can communicate the ideas (How can I explain this new information to someone?). Finally, by expressing themselves orally or in writing, they need to test the new knowledge out (Is this a good example of this idea?).

The new National Geographic Learning Academic Skills Series Reflect takes the learner through these stages in a supported way. For example, in a unit of Reflect Listening and Speaking 4 (at B1+ level), students listen to a lecture about the discovery of some marks next to cave paintings that date back some 20,000 years (see below). Their curiosity is provoked by the question: Do these marks on the wall have a meaning? Before they hear the answer, learners are first invited to talk about symbols they are familiar with – emojis – and how they use them. Later, having learned more about the evolution of symbols and discussed this, they are asked to devise their own symbol to go with a public notice and to present this to the class, explaining the reasons for their design.

It’s important to note that reflection and critical thinking in language learning are not just about evaluating texts and ideas. Throughout the process described above, students are also asked to reflect on language: they identify the forms used in models and then select the language they need to present their own ideas.

Building background knowledge

So, one way to avoid overwhelming learners with new topics is to encourage this constant reflection and refer them back to things, connected to the topic, that they can relate to personally. The other way is to help them to build subject knowledge in different areas.

Remember that background knowledge informs critical thinking at all levels. Students in their teens lack wide knowledge of the world and that makes it difficult for them to evaluate or compare ideas, since they don’t have much to compare them to! Background knowledge isn’t gained overnight. It comes from years of learning and paying attention to what’s going on. However, we can promote the building of it in two main ways: 1) with stimulating content and 2) by encouraging learner research, both inside and outside the classroom.

There are many good reasons for getting students to research information for themselves: they develop research skills, they practice their English, they build their knowledge, and, importantly, they then bring fresh ideas to the class for discussion.

In the series Reflect we build towards unit tasks that either draw on students’ existing knowledge and/or ask them to do more research on a given topic. That combination is the way to reassure them that they can approach new subjects with confidence – something that is vital for university study or a new work role.

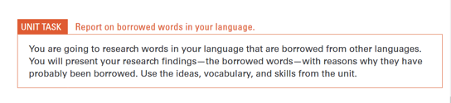

An example is this task from another unit in Reflect Listening and Speaking 4, where students have been learning about the topic of cultural borrowing.

Students will already know of some borrowed words, but they may need to research others. It’s likely that they will also need to research into why the words were borrowed.

For more on this topic, you can watch my full webinar recording HERE. Learn more about Reflect, from National Geographic Learning and download the interactive sampler.