Creating space for inquiry-based learning in the English language classroom can be difficult for teachers to navigate. We often feel caught between the spontaneity of the group before us as we explore an ongoing unit, and our need to meet curricular demands and make the best use of pedagogical materials.

Once we recognize inquiry in our course materials, we can leverage the materials to develop inquiry thinking in our students. Making connections between language learning and other class projects or inquiry-based units also allows us to lead more cohesive learning for our students. Read on to learn more about incorporating inquiry-based learning into your classroom!

What is inquiry-based learning?

Before looking into how inquiry applies to language learning contexts, let’s first review inquiry pedagogy. Inquiry-based learning is a methodology used by educational institutions and educators worldwide, and it is a cornerstone of the International Baccalaureate (IB) framework. It is widely recognized as an effective and inclusive approach to learning.

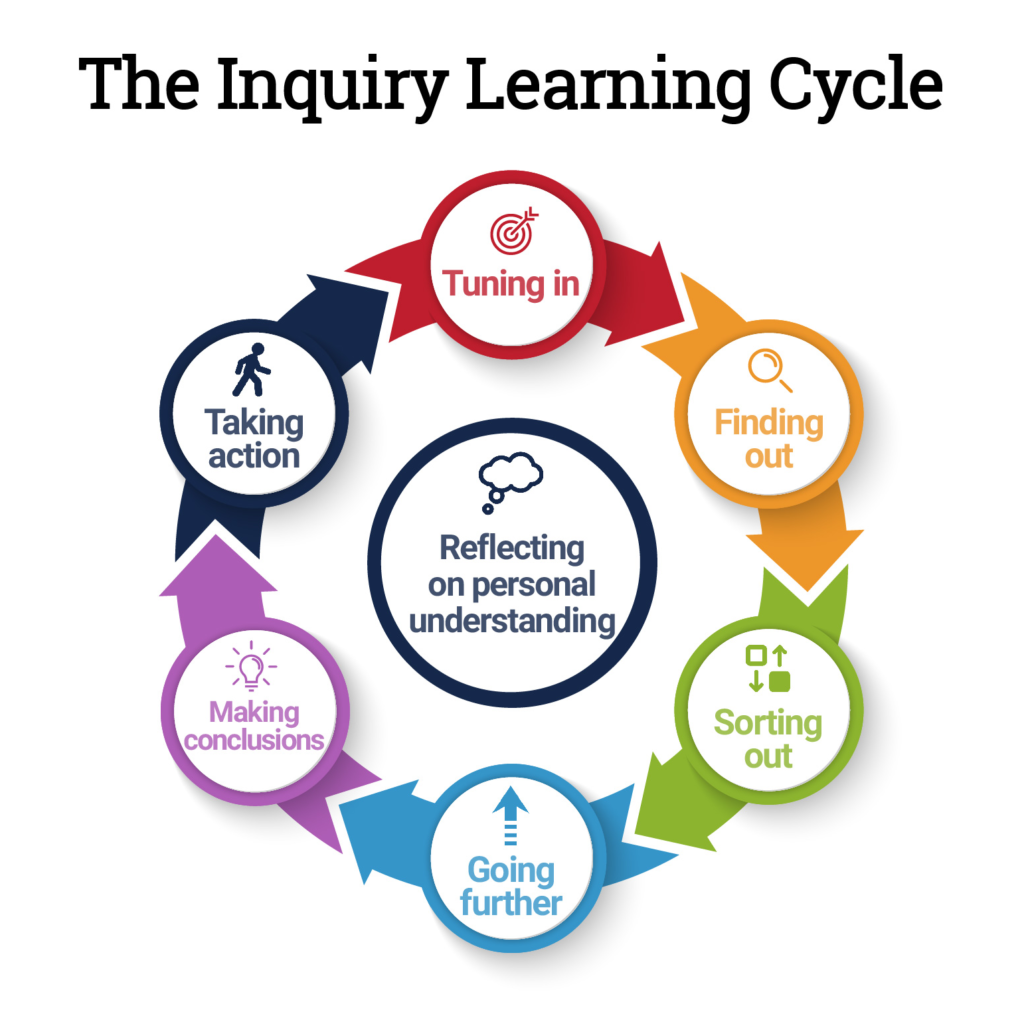

Inquiry-based methodologies are guided by the inquiry cycle, which begins with student-generated questions and ends with them taking meaningful action based on their learning. Students are, therefore, at the center of their learning journey. Their knowledge and experiences, curiosities, and preferences create the path which the inquiry will take.

The steps of the Inquiry Learning Cycle include:

- Tuning in: introducing themes and making personal connections, raising previous knowledge and asking initial questions

- Finding out: engaging in learning experiences, gathering new knowledge

- Sorting out: deciphering what information is relevant, revisiting initial questions

- Going Further: creating something new based on new understandings, sharing knowledge

- Making conclusions: drawing conclusions in relation to a central idea, making clear connections between the learner and the learning

- Taking meaningful action: changing a behavior or attitude, raising awareness or advocating for others based on our learning

In the International Baccalaureate framework, Units of Inquiry are driven by this cycle which prompts students to learn, reflect on their learning, and take action. Inquiries may last four to six weeks or longer, as they often do in the IB units of inquiry, or they can be as succinct as a single class period. Inquiry is a mindset that educators can apply within units of inquiry, or in standalone subject teaching, as we are guided by questions and provoke students to be deeply engaged and responsible for their own learning.

How can we encourage inquiry in an English language learning context?

The IB describes Inquiry in the following ways: it is purposeful and authentic, it incorporates problem solving, it furthers student learning through the generation of new questions and wonderings, and it connects personal experience to global opportunities and challenges.

Below we explore examples from the National Geographic Learning Programs Our World, Second Edition and Reach Higher, making connections to the IB’s description of inquiry-based learning, to show how your existing course materials can develop and support inquiry in your classroom.

Inquiry is purposeful and authentic.

Authentic learning means that what we are learning is relevant and connected to real-world contexts. When students strive to understand global issues such as environmental degradation, climate change, natural disaster response, and technological innovation, seeing them through both local and global lenses, we can be sure that these are worthwhile investigations that have meaning for the student and their community. The activities below help students understand the real-world topics of “lending a hand” to others and caring for animals, prompting students to connect these topics to their own lives.

Purposeful learning is learning with established, shared success criteria. Students take part in goal setting and receive personal feedback to measure their progress and set next steps. Projects with clear learning objectives, like the one below, help students work toward goals and measure their progress effectively. In this project from Our World, Second Edition, students create a poster about their favorite job and use the ‘Now I can…’ statements to reflect on what they have achieved by completing the project.

Inquiry incorporates problem solving.

Inquiry values problem solving by investigating issues rather than topics. It is important to encourage students to explore challenges and opportunities from multiple perspectives as they become effective problem solvers. Threatened species, for example, can be seen through the lens of conservationists, local residents, farmers, businesses, and national and international governmental initiatives. You might ask your students: “How do we balance each of these groups with their own interests? What is our role?”

In a language learning context, we can apply problem solving within the unit theme, and in our approach to grammar and language use, when we present students with examples of language constructions from which they will examine, discuss and deduce the pattern or rule.

Inquiry recognizes that problem solving takes time. This means as teachers we should not rush to give our students answers; instead, we should provide extended time for them to form answers and opinions. We should also expect these opinions to change as students’ understandings of issues, texts, characters, and plot develop over time.

Critical thinking skills are a necessary part of creative problem solving, and the development of these skills is supported throughout course materials like Reach Higher. The activities below show students how to ask robust questions and how to provide evidence for opinions and arguments, both of which are essential 21st century skills.

Inquiry generates new questions and wonderings.

Inquiry-based learning stimulates curiosity. As teachers, we are brave enough to know that we do not have the answers to all our students’ questions, but we can help them extend their initial questions to deeper thinking and wonderings.

Encourage curiosity with big, open-ended questions that provoke debate and thought. How do living things depend on each other? Why is the past important? Using strategies like ‘big questions’ and ‘Think, Pair, Share’, the course materials below call on every student to think about the question before sharing with a partner and then the whole group. This encourages all students to see themselves as responsible for contributing to their learning, presents a wide range of perspectives, and uncovers similarities and differences in their views.

Inquiry makes connections between local and global.

Inquiry calls on us to make connections between global and local contexts in the classroom. For example, this ‘Share What You Know’ unit introduction bridges global and local contexts by encouraging students to reflect on their own cultural traditions while connecting to the common thread of traditions and customs around the world.

Students are frequently prompted to connect their own experience to the themes that come up in the materials, such as in this activity, where they are activating prior knowledge before reading a text.

As an educator using inquiry teaching methods, you could explore international characters, art and songs or have your students make their own culturally relevant versions of songs to connect to references that young students are familiar with. This is just one way to celebrate our differences while drawing parallels between global and local cultures.

Conclusion

Inquiry is much more than asking and raising questions. It requires us to see learning a journey in which we are continually exploring new territory with our learners. Inquiry-minded course materials are necessary to create this kind of learning environment. Using materials such as the National Geographic Learning programs Our World and Reach Higher can help prioritize the development of critical thinking, capitalize on curiosity, and provoke students’ observations and wonderings. The rest is up to the magic of the teacher.

For more on inquiry-based learning, watch Melissa Zaramella’s webinar!