A few years ago I came across an extraordinary photo entitled Moonwalk by filmmaker and photographer Renan Ozturk. The image is of tightrope walker Andy Lewis, poised, midair, between two towering granite rocks in the state of Utah. The crisp, white, larger-than-life moon rises from the horizon in the background of the image. A million thoughts and questions raced through my mind after seeing the image. Where did the idea come from? How did the photographer know what day and time to take the photo? How did the climber and photographer communicate during the climb?

This is the kind of wonder and curiosity that drives deep learning, an approach that goes beyond learning facts to helping students understand big ideas and actively engaging them in the construction and communication of knowledge. It’s a central component of cross-curricular instruction. Over time, students taught with cross-curricular methods process content and language, including texts, at increasing levels of complexity, while building transferable skills and strategies such as critical and creative thinking. Cross-curricular instruction also connects to students’ lives and interests and incorporates joyful learning, both of which lead to higher levels of motivation and engagement in the classroom. All of this helps students develop deeper, broader language proficiency and effectively communicate across subjects, languages, and cultures.

For language teachers new to this approach, the idea of having to also teach materials from other content areas such as science, social studies, math, art and music can be daunting. Using wonder and curiosity as a key focal point can help ease the transition. Examples from Trailblazer, a new Primary ELT course from National Geographic Learning, illustrate how to integrate literacy and subject-matter content.

Use questions to nurture wonder and curiosity

Young students can be a bottomless well of questions and curiosity. However, that curiosity often disappears after a few years, especially in classrooms where teachers have the answers and students listen. There are many ways teachers can use questions to keep wonder and curiosity alive in the classroom. Teachers can model it by sharing their own questions about the topics that mean the most to them. A class Wonder Book, where students jot down questions they don’t have answers to, is another way.

Trailblazer builds wonder and curiosity into its materials in multiple ways. Each unit begins with a big question. In Trailblazer Starter Level, for example, a unit on everyday routines opens with an image of an orangutan brushing its teeth, putting a twist on the unit’s big question of “What do we do every day?” and inviting all kinds of questions about the image and how different people’s days can be. Targeted questions after each reading help students learn more about themselves and the world, building important life skills like cultural competence and self-regulation. And each unit ends with students reflecting on what they’ve learned, what they think, and what they are still curious about.

Harness the powers of reading

In the real world we’re constantly wondering about unknown concepts, and it’s often nonfiction text that fills those gaps and quenches our curiosity in the real world. 80-90% of what adults read is nonfiction, and for young learners who may be reluctant readers, nonfiction is often more appealing and accessible. However, good fiction can also immerse the reader in a world of wonder and curiosity. And when students get lost in the lives and stories of fictional characters, they build other important (and transferable!) skills, such as empathy and the ability to recognize organizational patterns.

Both fiction and nonfiction can be just plain fun to read, too (the kind of fun that has students rolling in their seats with laughter or shouting across the room “You have to see this!”). For example, in Trailblazer Starter Level, students may giggle at the idea of frogs with blond hair in a story about family and physical features.

In this reading passage from Trailblazer Level 3, students explore the country of Singapore, giving them the opportunity to experience the wonder and excitement of visiting a new place while learning about the travel article genre.

Reading now goes beyond just text-based materials, though. In an increasingly visual world, students need to develop skills and strategies to “read” (i.e. comprehend, evaluate, and analyze) what they see around them, both in school and on their own.

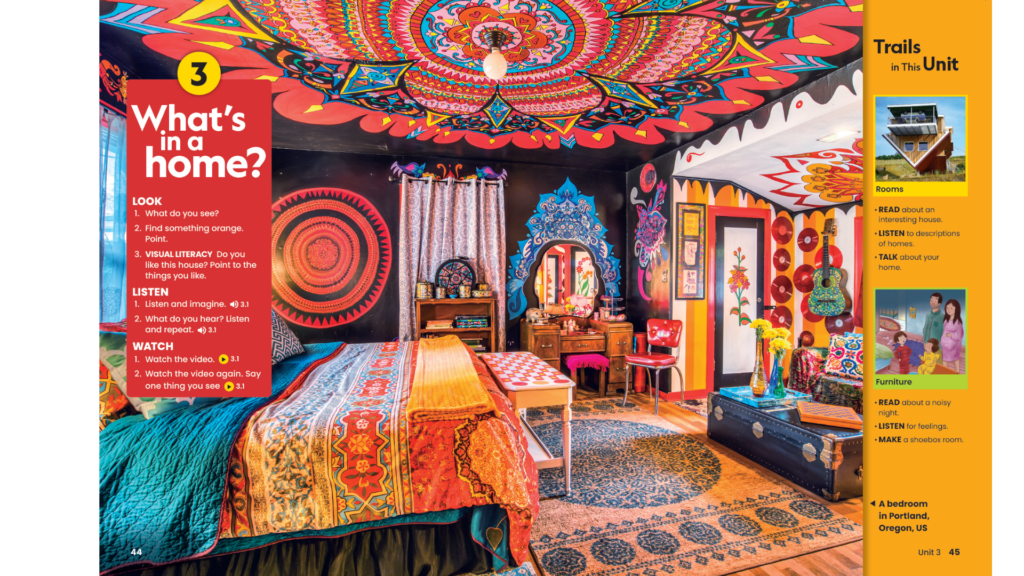

Throughout individual Trailblazer units, students interact critically and creatively with visuals such as illustrations and photos, charts, graphs, and maps. For example, in Trailblazer Starter Level they’re asked to point to the objects they like in a detailed image of a child’s bedroom.

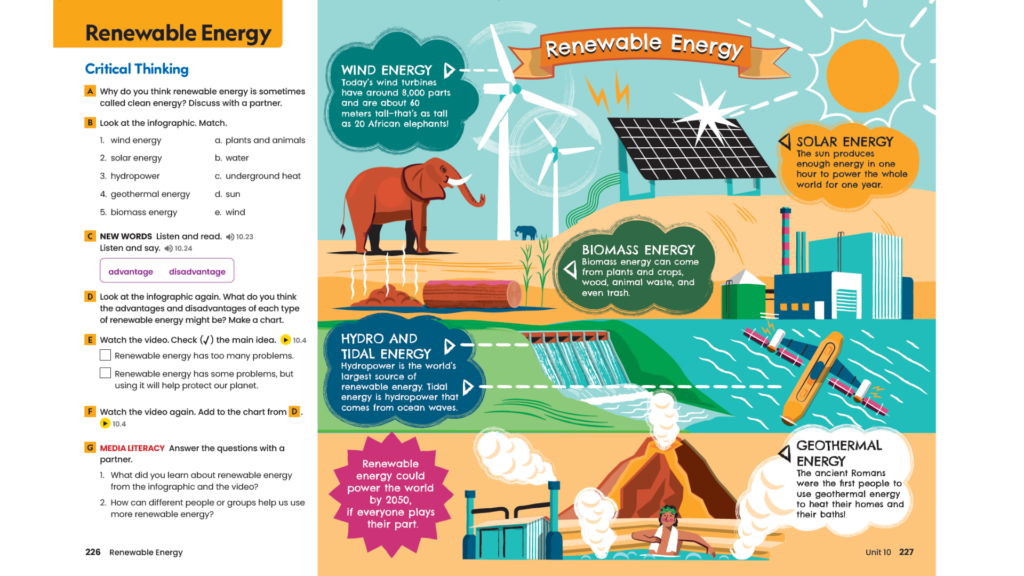

At higher levels, these critical thinking skills are specifically targeted at the end of each unit, where students dissect multiple forms of media connected to the unit’s themes. For example, in a unit in Trailblazer Level 3, students are encouraged to synthesize and explain different ideas about renewable energy by analyzing an infographic and then studying a video.

Teach transferable skills and strategies

Wonder and curiosity can only take students so far, however, unless they have a deep understanding of comprehension and text structure. Explicitly modeling and teaching reading strategies and characteristics of different genres help strengthen this understanding. Strategies such as guessing words from pictures and explicit instruction in the characteristics of genres can be taught alongside students’ very first exposure to English. As students progress through their studies, we can transition to more complex strategies such as identifying themes in a text. This also applies to strategies for the other core English language skills (speaking, listening, writing). And because the strategies are transferable to any reading material, they will continue to serve students long after they leave formal education for the real world.

Make learning joyful

Have you ever said a word so many times, rolling it, playfully, around your tongue, that it no longer made sense? Or have you ever joyfully jumped online to explore the etymology of a word?

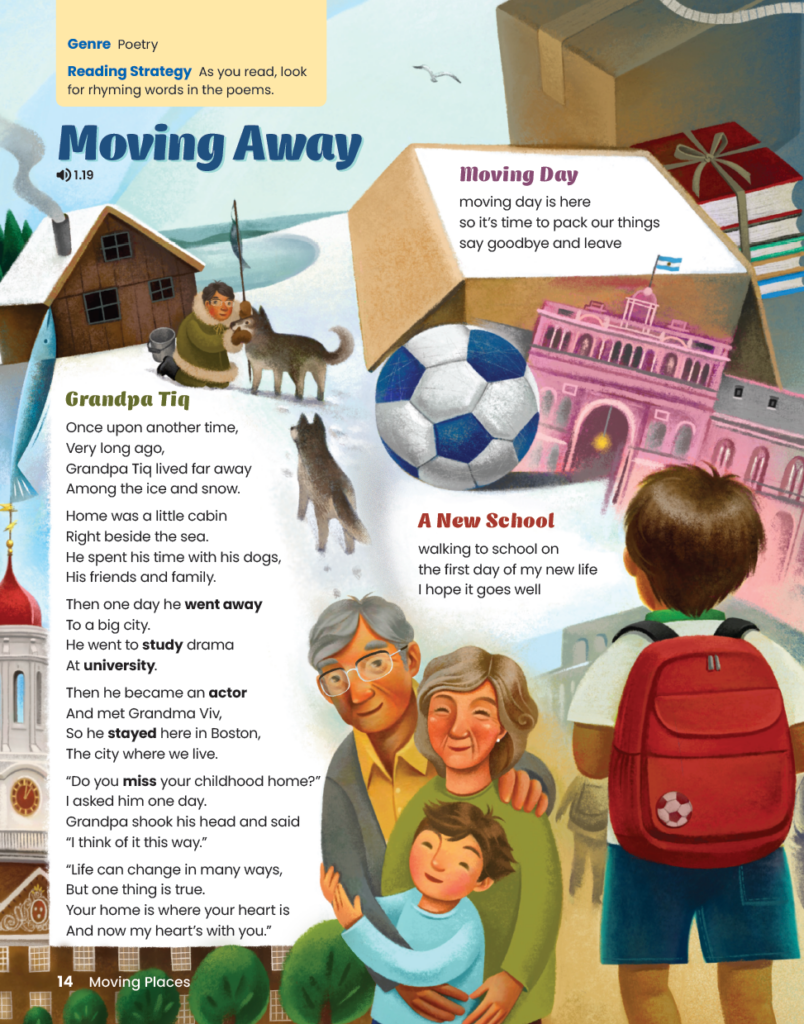

As adults (especially language teachers!) we’re curious about how words are related, how they interact and “play” with each other. Children have the same interest. Through phonics instruction, students explore sounds and words. Through rhyme, in songs and poetry, for example, phonics are reinforced and students develop skills for other important aspects of literacy, including word study, pronunciation, intonation, and fluency. These are skills that increase in complexity over time.

For example, at the Starter level of Trailblazer, the concept of rhyme is introduced. In Trailblazer Level 3, the focus on rhyme expands to a more advanced topic: evaluating rhyme patterns in forms of poetry such as haiku, limericks and narrative poems. Teachers also build on students’ passion for language when they share their own wonder and curiosity about language.

Teaching from a place of wonder and curiosity is a rewarding endeavor. It brings real life into the classroom while simultaneously bringing students’ learning to life. It also provides a framework for combining language, literacy and content area instruction in the language English classroom. It may involve learning new skills and strategies, but with the support of courses like Trailblazer, you’re well on the way to making the transition.

Trailblazer is a seven-level English language and literacy program that empowers and supports young learners to thrive in a multicultural world.

I simply loved reading the post. It’s magical that young learners can be inspired to motivate their learning skills through wonder and curiosity. I teach English to pre-intermediates belonging to multilingual backgrounds in rural India. What according to you should be the medium of instruction to make learning joyful, specially when learners have poor communication skills

I’m so glad to hear you liked the post! I think my answer is “it depends.” With pre-intermediate students you might be able to teach them more types of questions, and more quickly, if you use their home languages. One way to teach a variety of question types is to use a strategy called windows, mirrors, and sliding glass doors. With this strategy students ask questions about other people’s cultures and experiences (windows), their own cultures and experiences (mirrors), and about the worlds they enter when they read (sliding glass doors). If you use English as the medium of instruction, you probably won’t be able to teach as many types of questions as quickly, because students may first need to be taught the language and vocabulary necessary (such as wh- questions) to express their ideas. But taking your time doesn’t mean they’re expressing less wonder or curiosity. In the blog post above, there’s a page from Trailblazer that shows an elaborate, colorful bedroom. The first activity has students answer the question, “What do you see?” There are endless possibilities for exploring wonder and curiosity with just this one simple question. Students can use it to show what they see when they look out their front door, when they study a map, or when they think about the main character in a book they are reading. It’s a question that can be asked over and over again (the New York Times asks a similar question over and over. They have a regular feature called “What’s Going on in This Picture?” where students view an image and answer the question. It’s another great strategy to add wonder and curiosity to instruction on a regular basis.) Either way, with these ideas your students can start expressing wonder and curiosity quite quickly.

Hi, I am realy exited, to get more knowleadge about how to involve learning new skills and strategies with teens. All of theses metodologies are useful to share to everybody who wants to lean English.