Why do we have goals?

As teachers, we are encouraged to have goals for our lessons. Some teachers even write the goals on the board at the beginning of a lesson, so students can see them. For other teachers, their goals (also sometimes called aims) are written at the top of a lesson plan. However, not everyone agrees that goals are always necessarily a good thing. In her book ‘Designing language courses,’ Kathleen Graves outlines the contrasting views when it comes to goals. On the one hand, you have the teachers who believe that “You have to have clear goals before a lesson, otherwise how do you know what to teach or what you want the students to learn?” On the other hand, you also meet teachers who would say that “Goals get in the way because they force students to follow a path that might not be right for them.”

For me, there is an element of truth and common sense in both views. I think all our students rightly expect to attend a lesson where the teacher has a plan with an overall goal. At the same time, they want a teacher who will respond to their needs and therefore have the ability to be flexible in their planning and goal-setting.

What do our goals look like?

For the teacher, a goal should help you to plan the entire lesson organically. Graves suggests an approach of writing your goal and then listing your objectives. For example, your goal might be: “To enable students to tell a story in English.’ To achieve such a goal, you will need to list your objectives which might include, “Reviewing narrative tenses”, “Presenting vocabulary for the story”, and “Practising the use of discourse markers for a genre of story.”Another way to express your goals so that your students understand the aim of your lesson is to use an approach suggested by the educationalist Zoe Elder. She uses ‘so that’ in her goals in order to highlight the learning and its outcome. For example, if the goal of the lesson is that “By the end of the lesson, learners will have been introduced to the past simple tense,” Elder argues that it doesn’t explain to your learners the reason for doing it – it has no relevance to their real lives. So, you have to add the words ‘so that’ and give a reason. The goal might read like this: “By the end of the lesson, learners will have been introduced to the past simple tense so that they can talk about important dates in their lives.” Using the ‘so that’ approach makes a goal more relevant and ‘visible’ to the students.

Forward planning and backward planning

Most teachers are encouraged to plan their lessons so that they visualize each step of the lesson from the beginning to the end. For this reason, we tend to ‘forward plan’ our goals with a very idealized vision of how the lesson will proceed. But as my diagram above shows, our vision rarely matches the reality of a lesson!

The reality of a lesson is that we take all sorts of diversions because we are responding to the needs or learners along the way, and often we don’t quite achieve our goals. I don’t think this necessarily matters, because it’s the desire to achieve and master our goals which drive us and motivates us. However, rather than always plan forward from the beginning of a lesson, it’s often helpful to plan backwards; by this, I mean visualize what you want the students to be able to do at the end of a lesson and work backwards. For example, if you want the students to carry out a role-play in which they order a meal in a restaurant, then make that your starting point and work backwards, thinking of what they will need on the way to completing this role-play situation.

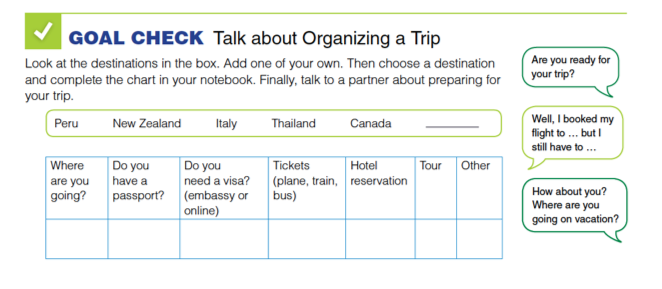

Showing students what success looks like

Teachers have different views about letting students know what the goals of the lessons are. Often, we write goals in a way in which we understand them as teachers but not with the intention that students will necessarily read or understand them. Some teachers write shortened – student-friendly – goals on the board at the beginning of a lesson so students can see what the general aim is. Some teachers don’t see a reason to share their goal with students. For me, it’s perhaps more effective to show students what success will look like by the end of a lesson. In this way, they understand the final goal. For example, you might write a list of can-do statements for the end of the lesson. Students can read them at the beginning of the class and then tick them at the end as a way to self-evaluate their progress. Here’s an example of such can-do statements for the aforementioned lesson on ordering a meal.

Another way of showing students what success looks like – especially for classes with a focus on speaking and listening – is by starting the lesson with a video of people doing the task that you want students to do by the end of the lesson. For example, it could be a video of people at a restaurant ordering food. Tell students that by the end of the lesson they will attempt to do the same thing. Using video in this way is motivating, and you are ‘showing’ students the final goal rather than telling them. It’s easy to make such a video by asking two colleagues to perform the task and recording it on your phone.

If you like some of the ideas in this post and you would like more, you can watch my full webinar on the topic below or visit the National Geographic Learning webinar archive.

John Hughes has written and co-authored many titles for National Geographic Learning including Life is the forthcoming third edition of World English. His website is www.johnhugheselt.com.

References

Graves, K. (2000) Designing Language Course National Geographic Learning

For Zoe Elder, visit https://fullonlearning.com/2012/10/01/constructing-learning-so-that-it-is-meaningful-and-purposeful

The diagram is based on an idea from this excellent book: Didau, D. (2015) What if everything you knew in education was wrong Crown House